The Common Sense Model (CSM) states that when a symptom is experienced, the person tries to make sense of the symptom by forming a cognitive representation. This representation is based on a set of beliefs that include:

- the identity of the symptom (e.g. a herniated disc)

- the cause of the symptom (e.g. heavy lifting in a bad position)

- the consequences of the symptom (e.g. physical incapacity)

- the controllability of the symptom (e.g. activity avoidance)

- the timeline of the symptom (e.g. will never go away). (1)

These beliefs can be formed either by previous direct experiences of the symptom, vicarious experiences observing others with similar symptoms, or information learned about the symptom from sources such as the media and clinicians. Beliefs about a symptom can, therefore, be formed before actually directly experiencing the symptom and will influence the representation of the symptom. (1)

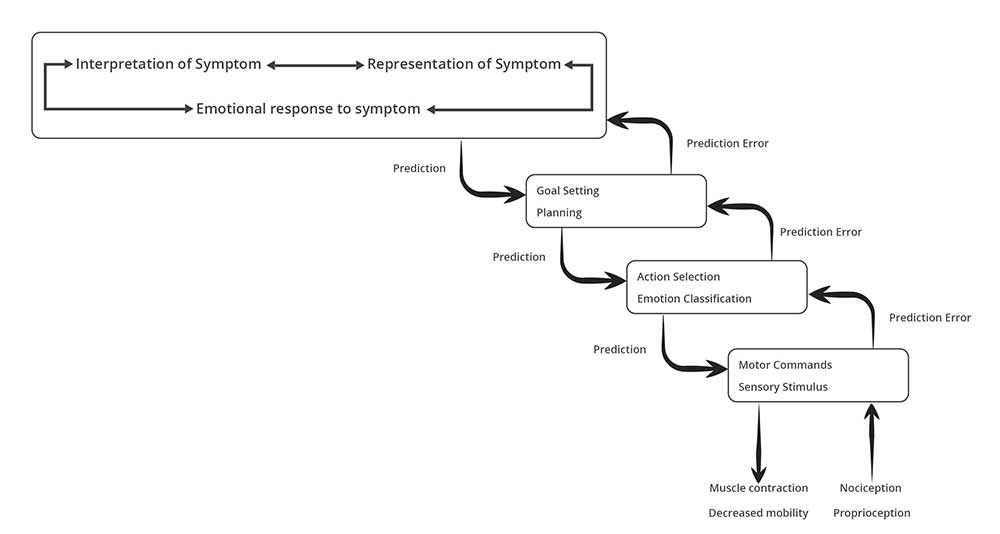

The representation of the symptom informs what actions will be undertaken to deal with the symptom. The representation of and the response to the symptom is multidimensional and involves features from sensory-discriminative, motivational-affective, and cognitive-evaluative dimensions. The Dispositionalism Model of Care incorporates all these characteristics in a a hierarchical cascade: (1)

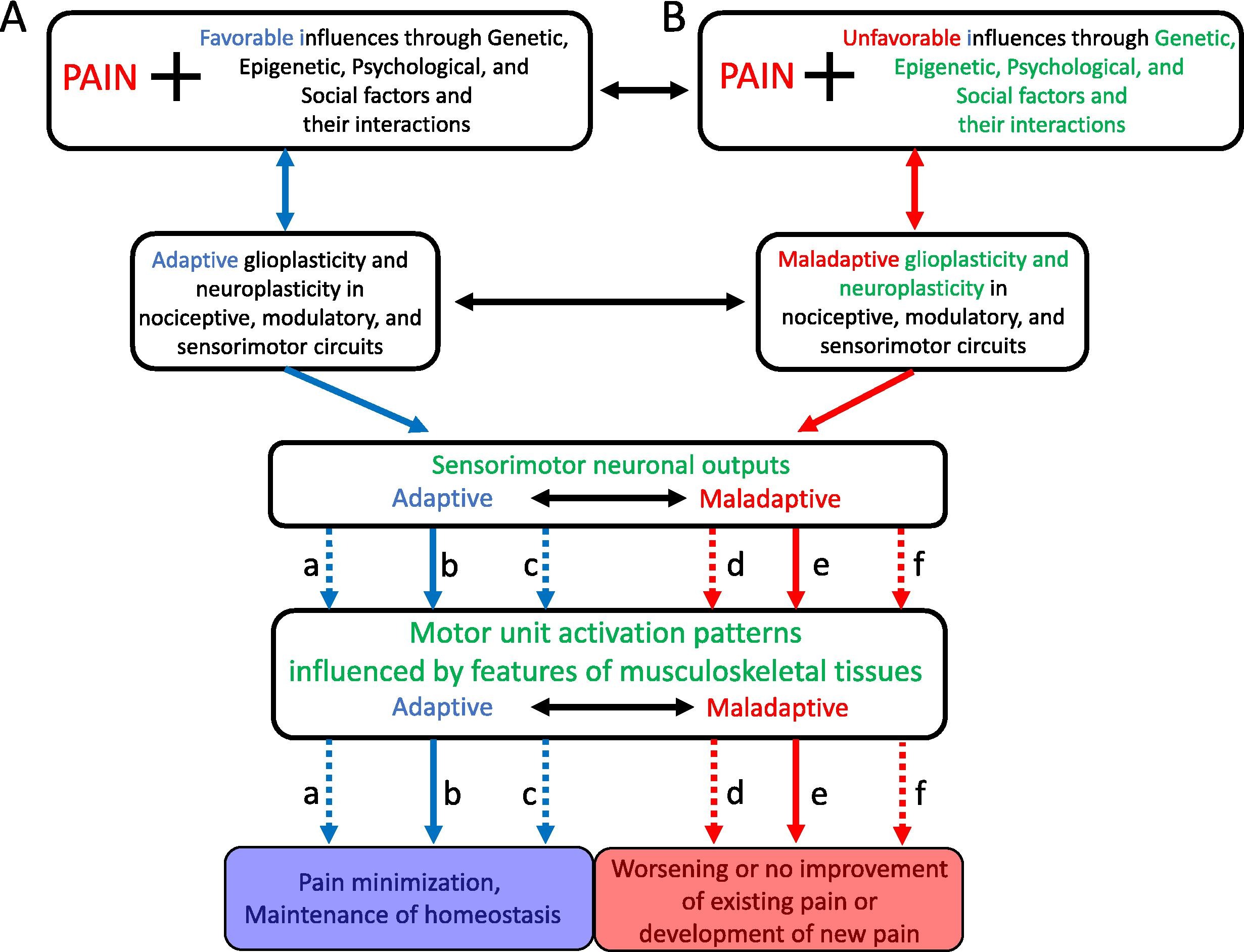

A new model of pain-sensorimotor interactions has been proposed in a just published article: Pain-sensorimotor interactions: New perspectives and a new model . This new model, the Theory of Pain-Sensorimotor Interactions (TOPSMI) also considers the sensory-discriminative, motivational-affective and cognitive-evaluative factors involved in pain sensorimotor interactions. It states that "pain is associated with plastic changes in the central nervous system (CNS) that lead to an activation pattern of motor units that contributes to the individual’s adaptive sensorimotor behavior. This activation pattern takes account of the biological, psychological, and social influences on the musculoskeletal tissues involved in sensorimotor behavior and on the plastic changes and the experience of pain in that individual. The pattern is normally optimized in terms of biomechanical advantage and metabolic cost related to the features of the individual’s musculoskeletal tissues and aims to minimize pain and any associated sensorimotor changes, and thereby maintain homeostasis. However, adverse biopsychosocial factors and their interactions may result in plastic CNS changes leading to less optimal, even maladaptive, sensorimotor changes producing motor unit activation patterns associated with the development of further pain."(2)

The TOPSMI brilliantly overlaps with and offers a detailed neurophysiological description of the sense-making process described in the Dispositionalism Model of Care:

Individuals can shift from favorable to unfavorable and from adaptive to maladaptive and vice versa depending on the current mix and weightings of factors that an individual might be experiencing (2).

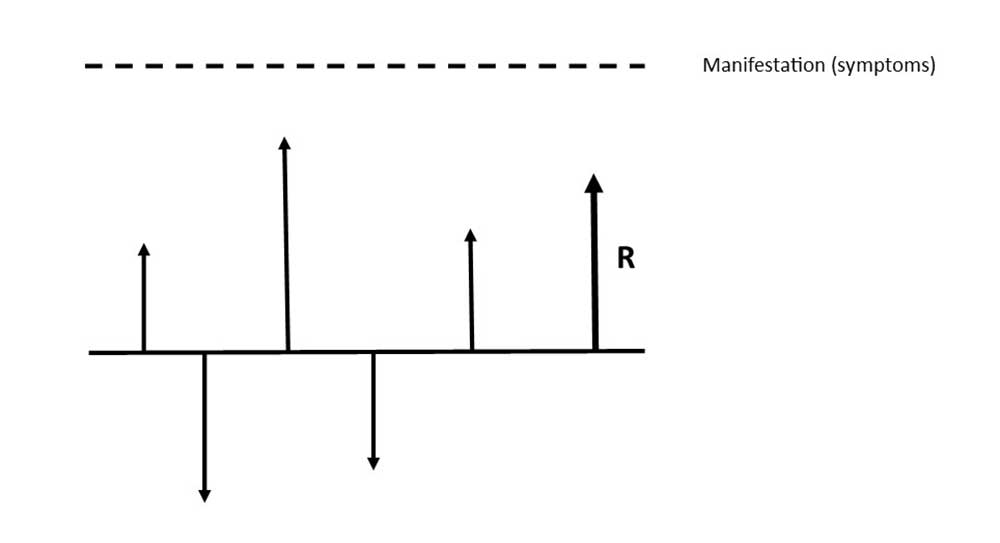

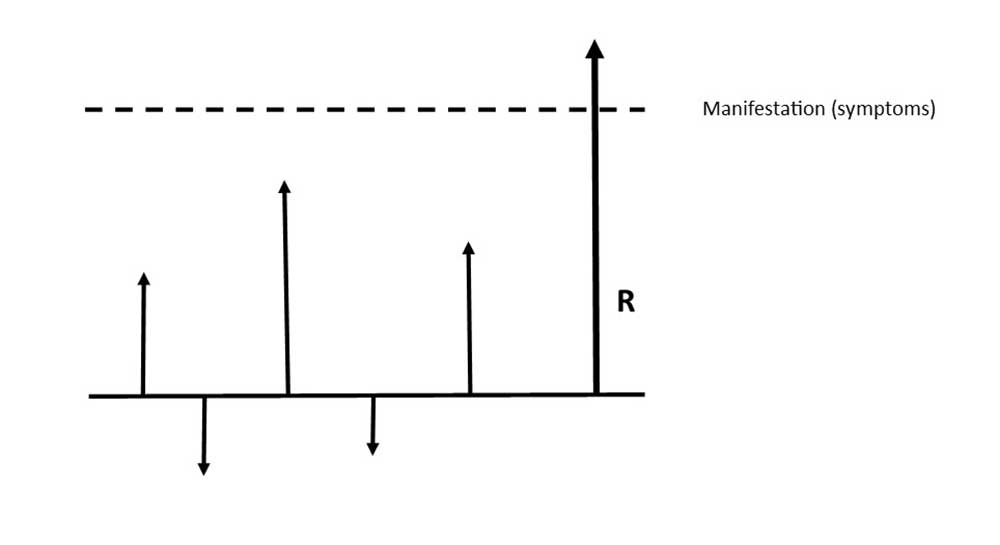

The vector model, as described in Dispositionalism in Musculoskeletal Care, reflects the changing context that influences symptoms' manifestation: (1)

From this perspective, it becomes clear that management strategies directed towards simply treating the muscles in pain are insufficient since the muscles are the end point of a large and complex sensorimotor system that is influenced by many biopsychosocial factors, and so a more holistic approach needs to be considered. (2)

1. VIANIN, M. Dispositionalism in Musculoskeletal Care: Understanding and Integrating Unique Characteristics of the Clinical Encounter to Optimize Patient Care. EVOLVE GLOBAL PUBLISHING. 2021

2. Murray, G.M. and Sessle, B.J. (2024) ‘Pain-sensorimotor interactions: New Perspectives and a new model’, Neurobiology of Pain, p. 100150. doi:10.1016/j.ynpai.2024.100150.